The Canterbury Tales (I Racconti di Canterbury) | 1972

- Locations |

- Kent;

- Cambridgeshire;

- Essex;

- Gloucestershire;

- Somerset;

- Suffolk;

- East Sussex;

- London;

- Italy

- DIRECTOR |

- Pier Paolo Pasolini

Discover where Pier Paolo Pasolini filmed his 1972 version of Chaucer's The Canterbury Tales around Southern England and in Italy.

The second part of Pasolini’s folksy, medieval ‘Trilogy of Life’ (coming between The Decameron and The Arabian Nights) conjures a strange, and defiantly non-historical, world from a wonderfully imaginative selection of real English locations and a company of, largely, non-actors with a sprinkling of the UK’s priceless character actors, including a soon-to-be-Dr Who, Tom Baker.

In the 1949 Ealing Studios classic Kind Hearts And Coronets, the decrepit Parson (Alec Guinness) gets to speak one of the great lines in cinema as he describes his West Window as having “all the exuberance of Chaucer without, happily, any of the concomitant crudities of his period”. In Pasolini’s version of The Canterbury Tales, he ensures that, happily, all of the concomitant crudities of the period are gloriously celebrated.

The director himself plays a genial Geoffrey Chaucer, wryly observing the varied pilgrims assembled at the Tabard Inn (which stood south of the River Thames in London’s Southwark) before departing on their devotional journey to the shrine of Thomas a Becket in the spiritual home of England’s church, Canterbury Cathedral in Kent.

The Tabard, which dated from 1307, stood in Talbot Yard next door to the George Inn (itself one of London’s oldest public houses) on Borough High Street, the ancient thoroughfare that led south from London Bridge to Canterbury. The George still thrives but all that remains of the Tabard is a blue plaque marking the site.

For the film, the ‘Tabard Inn’ is Coggeshall Grange Barn, Grange Hill, Coggeshall, about ten miles west of Colchester in Essex, dressed in a little half-timbered cladding. The 13th Century building – one of Europe's oldest timber-framed buildings – is now a National Trust property, housing an exhibition of wood-carving and agricultural implements.

First off, the Merchant’s Tale concerns the old and lascivious Sir January (Hugh Griffith, who got an Oscar for his Welsh sheikh in Ben Hur) and his decision to take for himself a, naturally much younger, wife.

Sir January’s estate is St Osyth’s Priory in the village of St Osyth, five miles west of Clacton-on-Sea on the B1027 in Essex, and that striking tower is the Darcy Tower, also known as the Abbott’s Tower.

Osyth, a nun, was beheaded by Viking raiders in the 7th century. These being sturdier days, before we’d all become wussy through modern medicine, the doughty Osyth simply picked up her head and returned to the nunnery before collapsing. Her ghost still walks along the priory walls – carrying her head, naturally. You’re unlikely to see her, though – the Priory is not currently open to the public, though there are plans to restore the estate and the situation may change.

Once Sir January opens his front door, the view down the street where, with a little help from a local rascal, he inspects the rump of a prospective bride, is Wells in Somerset.

It’s Vicar’s Close alongside Wells Cathedral, and the oldest complete street of 14th century houses in Europe. Built to accommodate members of the clergy from the cathedral, the houses are still occupied today.

Wells Cathedral itself is seen later in the film and in Shekhar Kapur’s historical epic Elizabeth: The Golden Age, with Cate Blanchett and in Bryan Singer's 2013 fantasy Jack The Giant Slayer. It’s emphatically not seen in Edgar Wright’s Hot Fuzz, with the all-too-recognisable Gothic silhouette digitally erased from the skyline of what was meant to be the little village of ‘Sanford’.

To complicate matters further, the interior of Sir January’s home is the vaulted undercroft of Battle Abbey, five miles northwest of Hastings in East Sussex.

As you might guess, the name and the location are no coincidence. The Benedictine abbey of Battle was founded by William the Conqueror in about 1071 as a memorial to the dead of the Battle of Hastings (1066 and all that...) and as atonement for the bloodshed. William insisted that the high altar of the abbey church be placed to mark where King Harold supposedly fell.

The jovial tone cools for a moment with the Friar’s Tale as Pasolini confronts the traditional hypocrisy of the established church. A coolly sinister presence (Pasolini regular Franco Citti) spies on men committing the unspeakable sin of ‘sodomy’. While the wealthy man simply pays off the authorities when he’s apprehended, the man who can’t afford to pay is arrested and executed.

To its credit, the Church of England allowed the horrific burning of the sinner on a griddle to be filmed in the cloisters of Canterbury Cathedral itself, in creepy silence punctured only by foodseller disturbing Citti’s cries of “Griddle cakes…”

The Cook’s Tale sees another member of Pasolini’s stock troupe, Ninetto Davoli, channeling Charlie Chaplin’s Tramp character as Peterkin.

For a moment we get to see the real Southwark, alongside the remains of the Great Hall of Winchester Palace, where the poor are queuing on the steps for food.

The Palace was once home to the Bishops of Winchester, who controlled Southwark. As this manor lay outside the jurisdiction of the City of London, activities that were forbidden within the city, including prostitution, animal baiting and theatre. Southwark thus became medieval London's entertainment district – Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre stood nearby. This all proved a nice little earner for the devout Bishops, and the local prostitutes became known as ‘Winchester Geese’.

The rascally Peterkin is chased by the 14th century equivalent of the Keystone Cops through the darkened, narrow walkways between the vast warehouses of the Victorian Shad Thames, which have now been smartened up and redeveloped to become luxury apartments and coffee shops.

The pursuers eventually plunge into the River Thames at Old Stairs, Wapping, in the old East End of London.

Wapping Old Stairs, a flight of stone steps giving watermen access to the Thames foreshore at low tide, run along the western side of the Town of Ramsgate pub, Wapping High Street, E1. Around here was Execution Dock, where, until 1830, pirates and other maritime criminals including the notorious Captain Kidd were hanged, or gibbeted, until three tides had passed over their bloated bodies.

Finally apprehended, the irrepressible Peterkin ends up being put in stocks in front of Layer Marney Tower, near Colchester in Essex. Dating from the early 16th century, Layer Marney is the tallest Tudor gatehouse in England.

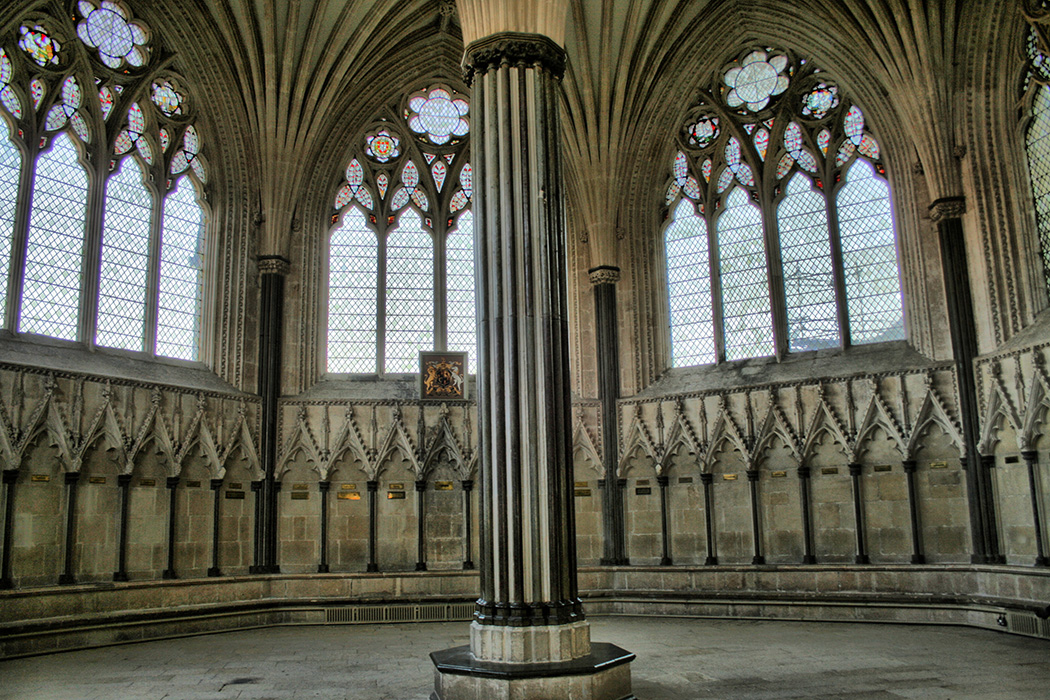

The Miller’s Tale sees randy suitor Absalon disporting himself at a dance held in the elaborately carved Chapter House of Wells Cathedral.

When his pal comes to tell him that the carpenter’s wife he’s been lusting after is all alone, he’s quickly off and running through the historic, narrow Trinity Lane, alongside Trinity College, part of the University in Cambridge.

His reward is not quite the delightful kiss he’s expecting, but he does get his wicked revenge though.

For the Wife of Bath’s tale, the village of Lavenham, ten miles south of Bury St Edmunds on the A1141 in Suffolk, stands in for the Somerset spa city. The Wife of Bath’s home (both exterior and interior), in which she exhausts her husband to the point of extinction, is Lavenham Guildhall.

The picturesque village is no stranger to the screen, having featured in Michael Reeves’ 1968 Witchfinder General, with Vincent Price, Stanley Kubrick’s masterpiece Barry Lyndon and more recently in Harry Potter And The Deathly Hallows Part I.

Eager for a new, and naturally much younger, husband, the lusty widow is soon marrying student Jenkin (Tom Baker) in the splendor of the Lady Chapel of Wells Cathedral.

On to the Reeve’s Tale, as Alan and John, a couple of students from Cambridge University do what students have always done and continue to do, look for an excuse to avoid studies and slope off for a bit of fun.

The scene is set with another Tudor gate, this time the Great Gate of St John's College, First Court, on St Johns Street, Cambridge.

Overcome with an earnest desire to watch their corn being ground, the pair get permission from their ailing tutor, and ride off to the local mill. Once there, they seem less interested in the technical details of flour production than in the miller’s wife and daughter.

The mill is Rolvenden Windmill, a grade II* listed Post mill on the B2086 road west of Rolvenden in Kent about 20 miles south of Maidstone. Built around 1580, the mill was in use until 1885, though the original roundhouse was demolished during WWI and, by the 1950s, had become increasingly derelict. It was restored in 1956 and is touchingly maintained as a memorial to a young local man killed in a road accident in 1955.

Privately owned and not open to the public, the mill was previously featured on screen in the 1967 musical Half a Sixpence, with Tommy Steele.

In the much darker Pardoner’s Tale, three lads whose friend has died naively decide to “look for Death” to take their revenge, with a predictable outcome.

The body of their companion is carried through the High Street of the historic village, Chipping Campden, ten miles south of Stratford-upon-Avon on the B4035 in Gloucestershire.

The three seem to travel a long way in their quest. It’s alongside St Thomas a Becket Church, on the bleak Romney Marsh near Fairfield in Kent that they ask an old man (Alan Webb) where they can find death. The village that this strangely isolated church once served has long since disappeared.

When the old man directs the three to a stash of hidden treasure, one of the number immediately rushes back to Chipping Campden, to buy rat poison from an apothecary in the historic Chipping Campden Market Hall. Needless to say, the three do indeed meet death.

The small stone market hall, open to the elements, was built in 1627 for Sir Baptist Hicks to provide shelter for local merchants and farmers to sell their wares. Now listed Grade I and managed by the National Trust, it’s used by local traders to this day.

The last story, the scurrilous Summoner’s Tale, which includes the climactic ‘Hell’ sequence with the giant Devil farting friars from his arse (I told you it contained the crudities of his period), was filmed on the fittingly sulfurous, volcanic slopes of Mount Etna in Sicily.

The film ends as the pilgrims arrive at Canterbury Cathedral. Originally founded in 597 and rebuilt between 1070 and 1077, the Cathedral was extended to accommodate this flow of visitors to the shrine of Thomas a Becket, the archbishop murdered in the cathedral by followers of King Henry II in 1170 and subsequently canonised to become St Thomas Becket.

Canterbury Cathedral had previously been seen on screen in Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger's quirky 1944 A Canterbury Tale and in the 1963 musical, I Could Go On Singing, with Judy Garland.